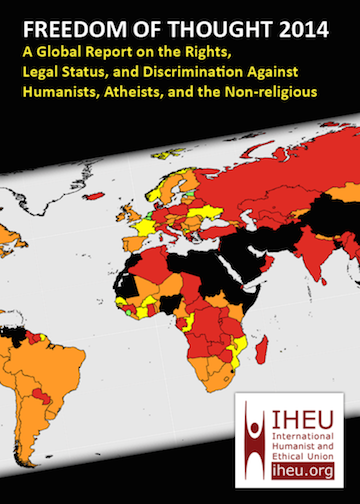

The International Humanist and Ethical Union has released its Freedom of Thought Report 2014, which is an annual global report on discrimination against humanists, atheists, and the non-religious, and their human rights and legal status. Atheist Ireland contributed information about religious discrimination in Ireland to the process of developing the Report.

The International Humanist and Ethical Union has released its Freedom of Thought Report 2014, which is an annual global report on discrimination against humanists, atheists, and the non-religious, and their human rights and legal status. Atheist Ireland contributed information about religious discrimination in Ireland to the process of developing the Report.

Overall, the Report concludes that the overwhelming majority of countries fail to respect the rights of atheists and freethinkers. For example, there are laws that deny atheists’ right to exist, revoke their right to citizenship, restrict their right to marry, obstruct their access to or experience of public education, prohibit them from holding public office, prevent them from working for the state, or criminalize the expression of their views on and criticism of religion. In the worst cases, the state or non-state actors may execute the non-religious for leaving the religion of their parents.

The report rates Ireland as suffering from systemic discrimination against atheists, humanists and the non-religious. The section on Ireland concludes with this testimony from Jane Donnelly, Atheist Ireland’s Human Rights Officer:

“In Ireland the non-religious are now the second largest group in Society after Roman Catholics but still face religious discrimination. The Irish Constitution begins with “In the name of the Holy Trinity” and Catholic social policy is reflected in many of our laws. The Catholic Church in Ireland controls the vast majority of publicly funded schools which have exemptions from equality laws. A religious oath is required to take up the office of President or to become a Judge and in 2010 Ireland introduced a new blasphemy law. It is time for Ireland to realise that it must comply with its human rights obligations and ensure that all citizens have rights regardless of their religious or philosophical convictions.”

— Jane Donnelly, Atheist Ireland

Here is what the Report says about Ireland:

- Ireland

- Rating: Systemic Discrimination

- Sectarian history

- Constitution and law

- Religious pressure – but it’s on the wane

- Belief demographics

- Education

- Religious Education and Instruction

- No provision for the non-religious

- Blasphemy Law (2009)

- Recent Constitutional Developments

- Abortion

- Testimonies

1. Ireland

The Republic of Ireland is a country of about 4.5 million people. It achieved de facto independence from the UK in 1922, when the southern, largely Catholic 26 counties formed the Irish Free State within the British Commonwealth (the 6 predominantly Protestant countries of the north east formed Northern Ireland.) A fully sovereign Republic in the south was declared in 1949.

2. Rating: Systemic Discrimination

General systemic issues

- There is systematic religious privilege

- Preferential treatment is given to a religion or religion in general

- Religious groups control some public or social services

- State-funding of religious institutions or salaries, or discriminatory tax exemptions

Freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief; Establishment of religion

- Official symbolic deference to religion

Education

- There is state funding of at least some religious schools

- Religious schools have powers to discriminate in admissions or employment

Family, community,religious courts and tribunals

- Insufficient information or detail not included in this report

Expression, advocacy of humanist values

- Criticism of religion is restricted in law or a de facto ‘blasphemy’ law is in effect

3. Sectarian history

The dominant religion in Ireland has traditionally been Roman Catholicism, and the Catholic Church has influenced the island since the 4th century. Much of the island remained Catholic despite the reformation in England and Irish history has been dominated by ethno-religious conflicts between Catholics and Protestants. Resistance to British rule largely came from within the Catholic community (with some notable exceptions).

Under British administration, the Catholic majority experienced high levels of legal and social discrimination, including restrictions on land ownership, limitations on religious practice and being barred from various political positions. Despite reforms, by the early 20th century discrimination was still widespread and was one of the factors fuelling an independence movement dominated by practising Catholics.

The Catholic Church came to be dominant in both the political system and civil society in the first decades of independence. Over 92% of people were recognised as Catholic, and this would only grow as many protestants left the Free State. The church also wielded significant political influence.

4. Constitution and law

The constitution and other laws and policies protect freedom of thought, conscience and religion, as well as freedom of expression, assembly and association. However, anti-blasphemy laws and state sponsorship of religion are in place (see below).

The Constitution of Ireland is an ostensibly secular, guaranteeing freedom of religion explicitly stating that “no law may be made either directly or indirectly to endow any religion”. However, the preamble is far from secular:

“In the Name of the Most Holy Trinity, from Whom is all authority and to Whom, as our final end, all actions both of men and States must be referred…”

Whilst, article 44 (section 1) states:

“The State acknowledges that the homage of public worship is due to Almighty God. It shall hold His Name in reverence, and shall respect and honour religion.”

Article 12, section 8 of the constitution demands that on taking office the President should declare:

“In the presence of Almighty God I do solemnly and sincerely promise and declare that I will maintain the Constitution of Ireland and uphold its laws, that I will fulfil my duties faithfully and conscientiously in accordance with the Constitution and the law, and that I will dedicate my abilities to the service and welfare of the people of Ireland. May God direct and sustain me.”

The constitution also demands a similar declaration be made by incoming judges. No secular alternative is offered, effectively precluding atheists and agnostics from these important positions.

The report, “Equality for the Non Religious (2013)”, conducted by the Humanist Association of Ireland said of the Constitution:

“If the Constitution is to be a document to speak for all citizens, its current wording fails that test.”

In July 2014 the UN Human Rights Committee criticised the Irish Government for not changing the religious Oath required for Judges.

5. Religious pressure – but it’s on the wane

Pressure from the Church resulted in bans on contraception (partially legalised in 1978) and divorce (legalised in 1997). Abortion remains illegal under the constitution and the last attempt at reform narrowly failed in a 2002 referendum. Censorship of books, plays, television and films was also widespread, especially those not congruent with Catholic dogma.

In recent years the Church’s influence on Irish civil society has significantly waned. This is in part due to changes in demographics, urbanisation, and the country’s emergence into the global economy. A series of Church scandals going back to the late 1990s, especially the Catholic Church Child Sex abuse appear to have played a huge role in plummeting church attendance. Whereas, back in the 1970s attendance had been recorded at 90%, recent surveys have recorded national weekly attendance at 30% with some parts of Dublin reporting attendance at less than 15% (though the 2011 census had 86% of the population identifying as Catholic).

6. Belief demographics

With the recent decline in the influence of the Church, the number of non-religious people has increased. According to the Census 2011 results:

“The total of those with no religion, atheists and agnostics increased more than four-fold between 1991 and 2011 to stand at 277,237 in 2011.”

This figure represents 6% of the population. 84.2% of people still identified with the Catholic Church. However, recent opinion polls have suggested that these figures are not representative of religious practice. For example the 2012 Global Index on Religiosity and Atheism recorded that only 47% of those asked described themselves as “a religious person”, 44% described themselves as “not religious” and %10 as “confirmed atheists”.

7. Education

The Church had dominated education in the country since British reforms in the 1830s, a dominance that was expanded after independence. Currently, despite the church’s decline in influence within the country as a whole, both the Primary and Secondary School sector is almost entirely controlled by religious organisations. Despite attempts by the current government to diminish some of the Catholic Church’s influence, nearly 90% of primary schools are Catholic run and nearly half of Second Level schools are managed solely by the Catholic Church. The remaining schools are managed by Education & Training Boards and are described as multi-denominational state schools but nearly one hundred of these are run in partnership with the Catholic Church or the Church of Ireland.

The government has made some moves to end the Catholic Church’s virtual monopoly on Ireland’s education system and organisations like “Educate Together” have established a small number of “Multi Denominational” schools, run independently of any religious patron.

However, some “Multi Denominational” schools can still be involved in “faith formation” and their facilities can still be used for religious practices outside of school hours, if requested by parents.

There are currently no fully secular or “Non Denominational” schools in Ireland.

Publicly funded schools run by religious groups are permitted to refuse admission to a student not of that religious group if the school can prove the refusal is essential to the maintenance of the “ethos” of the school. Equalities legislation recognises nine “grounds” for discrimination which are gender, marital status, family status, sexual orientation, religion, age, disability, race and membership of the Traveller community. However, a school’s admission policy can be exempt from the religious ground. According to the Equality Authority’s own equalities guidance:

“A second exemption concerns schools where the objective is to provide education in an environment that promotes certain religious values. A school that has this objective can admit a student of a particular religious denomination in preference to other students”.

Though non-denominational schools exist, they are few in number and places are in short supply. The Humanist Association of Ireland (an IHEU member organization) state in their report “Equality for Non-Religious People” that:

“The reality for many families is one of lack of choice of school in their locality and many are effectively forced to send their children to schools of a particular religious denomination whose ethos is not in conformity with their own”

Furthermore, religious schools may select its staff based on their religious beliefs. For example, section 12 of the 1998 Employment Equality act allows bodies to discriminate on religious grounds if “the provision of services in an environment which promotes certain religious values”. Most teachers in Ireland are expected to teach religious (Catholic) instruction.

According to the Humanist Association of Ireland:

“Despite the increasingly diverse society…the only route available…for an individual seeking qualification as a primary teacher is through a course taken at a college owned by a religious denomination.”

8. Religious Education and Instruction

Though the rest of the state’s national Curriculum is administered by the governmental “National Council for Curriculum and Assessment”, according to the council, “The development of curriculum for Religious education remains the responsibility of the different church authorities.”

This is usually, though not always, the Catholic Church. Parents have a constitutional right to exempt their children from religious instruction in schools, but parents who do not wish to have their children attend religious classes in school are routinely asked to supervise them personally during school hours because schools will not do so.

However, the curriculum at all levels, as it stands, does include discussions of humanism and atheism and covers the more general “Challenges to Faith”.

9. No provision for the non-religious

In August 2014 the UN Human Rights Committee criticised the Irish government for its lack of provision of education to the non-religious and religious minorities stating:

“The Human Rights Committee is concerned about the slow progress in increasing access to secular education through the establishment of non-denominational schools, divestment of the patronage of schools and the phasing out of integrated religious curricula in schools accommodating minority faith or non-faith children.”

10. Blasphemy Law (2009)

Article 40 of the constitution, though protecting freedom of religion and consciousness, also states that “The publication or utterance of blasphemous, seditious, or indecent matter is an offence which shall be punishable in accordance with law”. In an attempt to clarify the constitutional implications of the blasphemy regulations within the constitution, lawmakers inserted a section on blasphemy to the Defamation Act of 2009. Section 36 of the act criminalizes the publishing or utterance of “blasphemous matter” and imposes a maximum fine of €25,000.Under the act a person has produced “blasphemous matter” if –

“(a) he or she publishes or utters matter that is grossly abusive or insulting in relation to matters held sacred by any religion, thereby causing outrage among a substantial number of the adherents of that religion, and

(b) he or she intends, by the publication or utterance of the matter concerned, to cause such outrage”.

Protection exists if:

“a reasonable person would find genuine literary, artistic, political, scientific, or academic value in the matter to which the offence relates”.

So far, there has been no recorded prosecution under the Blasphemy Law. However, Islamic states and proponents of “blasphemy” and “defamation of religion” laws have pointed towards the Irish law to justify their own draconian legislation.

11. Recent Constitutional Developments

The Constitutional Convention, formed in December 2012, was convened to review various elements to the constitution, including the blasphemy section. The convention took submissions in favour of removing the blasphemy section from secular organisations Atheist Ireland and the Humanist Association of Ireland. The Council of Irish Churches, an organisation representing an array of Christian denominations, also offered a submission in favour of repeal describing the blasphemy clause as “obsolete”. The Knights of Saint Columbanus and the Islamic Cultural Centre of Ireland argued in favour of retention. The convention voted in favour of deletion of the clause but also recommended it be replaced with a prohibition against “incitement to religious hatred”. It was confirmed that repeal of the Blasphemy Section will be put to a referendum sometime in 2015.

The report, “Equality for the Non Religious (2013)”, conducted by the Humanist Association of Ireland said of the Constitution –

“If the Constitution is to be a document to speak for all citizens, its current wording fails that test. If the Constitution is to be a document to speak for all citizens, its current wording fails that test.”

12. Abortion

Abortion has been illegal in Ireland since British rule and remained so after independence. Recent legislation has made exception in cases where the mother’s life is at risk. In part to prevent future attempts to legalise abortion, the eighth was passed by referendum and acknowledged –

“the right to life of the unborn and, with due regard to the equal right to life of the mother, guarantees in its laws to respect, and, as far as practicable, by its laws to defend and vindicate that right”

The most recent referendum, in 2002, to amend the constitution failed by a margin of less than 1%. Many Irish women choose to have an abortion in the UK and there has been significant and legal wrangling debate over the how the right to travel might conflict with the right to life of the foetus.

13. Testimonies

“In Ireland the non-religious are now the second largest group in Society after Roman Catholics but still face religious discrimination. The Irish Constitution begins with “In the name of the Holy Trinity” and Catholic social policy is reflected in many of our laws. The Catholic Church in Ireland controls the vast majority of publicly funded schools which have exemptions from equality laws. A religious oath is required to take up the office of President or to become a Judge and in 2010 Ireland introduced a new blasphemy law. It is time for Ireland to realise that it must comply with its human rights obligations and ensure that all citizens have rights regardless of their religious or philosophical convictions.”

— Jane Donnelly, Atheist Ireland

14. Full Report

The full report, Freedom of Thought 2014: A Global Report on Discrimination Against Humanists, Atheists, and the Non-religious; Their Human Rights and Legal Status, was created by the International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU). It includes ratings and evaluations for all countries in a comprehensive 542-page resource.

In building this survey they use the global human rights agreements that most affect freethinkers as freethinkers: the right to freedom of thought, conscience, or religion; the right to freedom of expression; and, to some extent, the rights to freedom of assembly and association. And they try to consider national laws that compromise or violate any human rights.

If you have updates, additions or corrections for the report please email report@IHEU.org or visit the report website at http://freethoughtreport.com.

You can download the full report here.