Atheist Ireland has made the following submission about Freedom of Thought to Ahmed Shaheed, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief. Mr Shaheed had called for inputs to a report he is compiling for the UN General Assembly on the topic.

Contents

- Internal — Freedom of Thought

- External — Manifestation of Thought

- Conflict of Rights when Manifesting Thought

- Analysis of the Situation in Practice

4.1 The Right to Freedom of Thought

4.2 The Right to Not Reveal Your Thoughts

4.3 The Right to Not Be Penalised for Your Thoughts

4.4 The Right to Receive Information

4.5 The Right to Nonreligious Philosophical Convictions

4.6 The Situation in Ireland

4.7 The Irish Education System

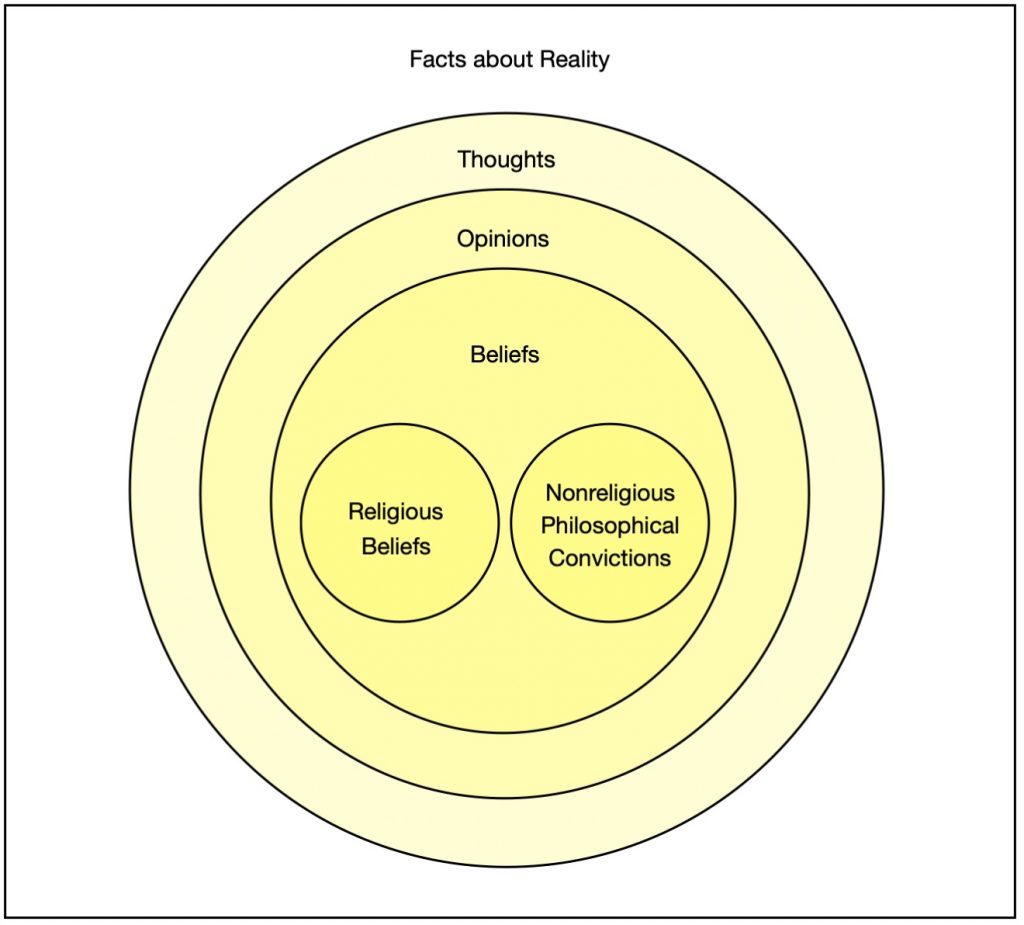

1. Internal — Freedom of Thought

Freedom of opinion and belief are particular examples of freedom of thought. A thought is any idea that occurs in your mind. Two examples of thoughts are:

- An opinion, which is a view or judgment about something, and

- A belief, which is an acceptance that something is true or corresponds with reality.

In human rights terms, the words “religion and belief” refer to two subsets of all beliefs — religious beliefs and nonreligious philosophical convictions about life that amount to a coherent worldview and can shape a person’s conscience.

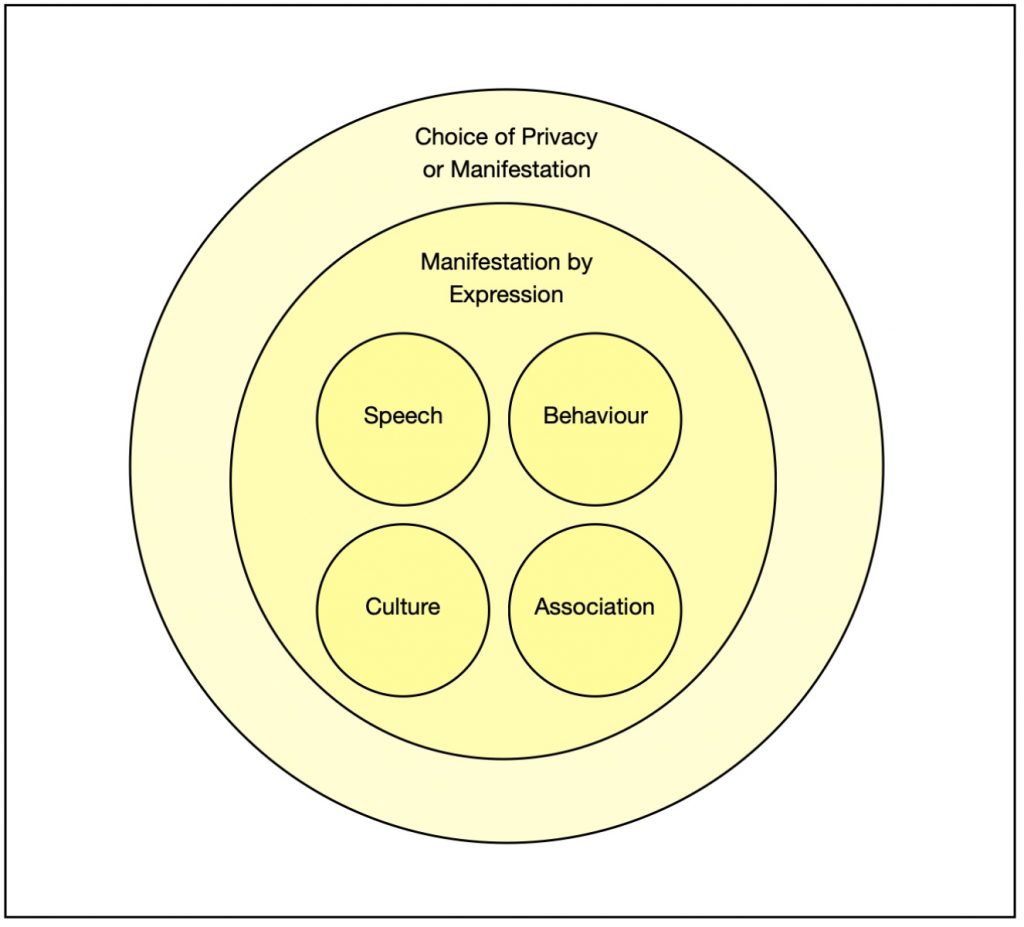

2. External — Manifestation of Thought

Freedom of expression, speech, behaviour, culture, and association are particular examples of the manifestation of freedom of thought.

- You have the choice to keep your thoughts private or to manifest them by making them clear to others.

- You can choose to manifest your thoughts by expressing them. This can include speech, behaviour, culture, and association.

Choosing whether or how to manifest your thoughts also has a correlation with freedom of conscience.

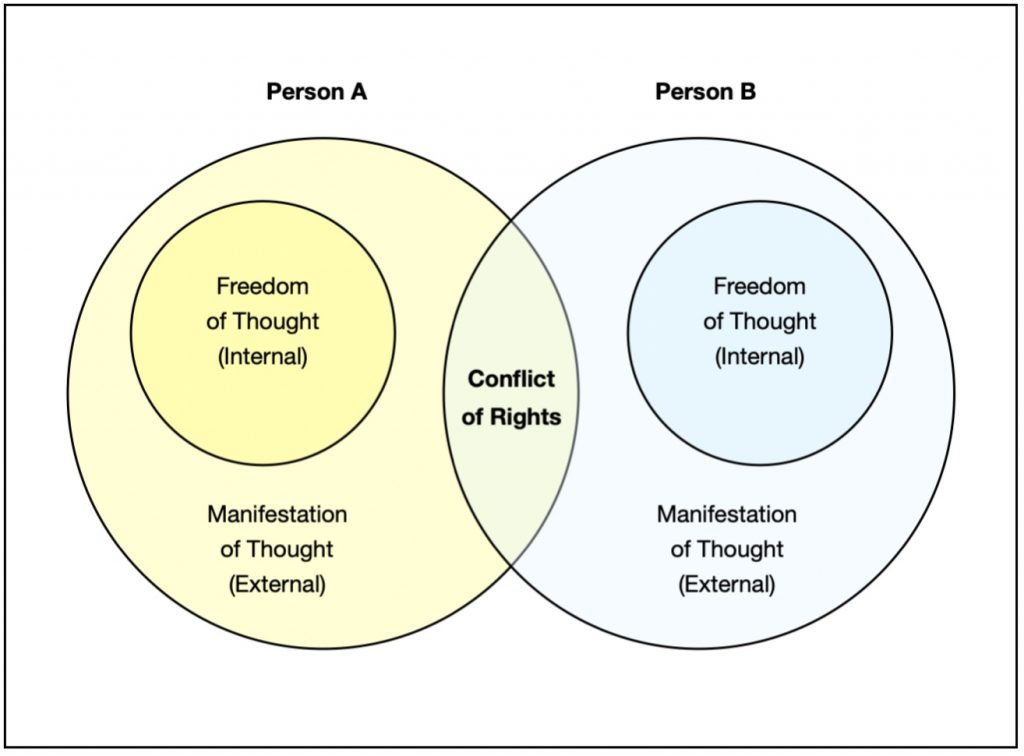

3. Conflict of Rights when Manifesting Thought

- Each person’s internal Freedom of Thought is inviolable.

- Each person’s external Manifestation of Thought is limited by the requirement to not violate the rights of others.

This can create conflicts of rights when different people manifest their thoughts through expression, speech, behaviour, culture, or association. The conflict can be made more difficult when the manifestation of thoughts contravene a person’s conscience.

4. Analysis of the Situation in Practice

4.1 The Right to Freedom of Thought

The right to Freedom of Thought is part of Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). It is an absolute right which cannot be interfered with in any circumstances.

4.2 The Right to Not Reveal Your Thoughts

Many States do not recognise the right to not reveal your thoughts, particularly when it comes to religious beliefs or nonreligious philosophical convictions.

This includes the right to not be forced to behave publicly in a manner that others can infer, even indirectly, what your religious beliefs or nonreligious philosophical convictions are.

- This can happen where the State forces people to take religious oaths, or to publicly choose between taking a religious oath and a secular declaration, in order to take up public office or in any interaction with the State.

- It can happen where the State is carrying out its obligation to provide education by delegating the running of schools to religious bodies that are allowed to run the schools in accordance with their religious ethos.

- It can happen where technological advances enable the State and/or private corporations to indirectly monitor people’s thoughts, by tracking their online behaviour including their social media and web browsing history (as well as more directly through monitoring their online search history, where most people would have an expectation of privacy).

- It may happen on a more serious level in the future, as further technological advances may enable neuroscience to decode what you are thinking from your brain activity.

It is important that the right to not reveal your thoughts is protected under the right to freedom of thought, which is absolute, and not merely under the right to privacy, which has to be balanced against other rights.

4.3 The Right to Not Be Penalised for Your Thoughts

Laws against what some people describe as ‘hate crimes’ must be based on human rights standards. We cannot change how people think and feel by making it illegal. We should tackle prejudice against groups through education and community leadership, and tackle prejudice-motivated crime through the law, where the prejudice is an aggravating factor as a motive for an existing crime.

Laws should be accurate, understandable, and enforceable. Their words and definitions should be coherent, universal and inclusive, with clear and justified boundaries, and free from ideological assumptions. A person should be able to know whether or not they are breaking it. Laws based on ambiguous or emotive words such as ‘hate’ cannot do this.

Social media means that many young people express their thoughts publicly. Years later they can be shamed for the expression of that thought even though they were immature when they expressed it. In some case people have been suspended and made apologise publicly for expressing a thought when they were young. There is a lack of understanding of the fact that most people change their thoughts as they grow and mature.

People can also be disproportionally penalised on social media or in their places of employment for expressing their current thoughts, where those thoughts are not illegal, but where other people find them offensive or deem them to be thoughts that should not be expressed. People can be pressured or shamed into not expressing their thoughts and beliefs, or into expressing thoughts and beliefs that they do not share, in their social media postings and bios.

4.4 The Right to Receive Information

The right to freedom of thought implies to right to seek and receive information that can inform the development of your thoughts.

This is recognised by resolution 59 of the UN General Assembly adopted in 1946, as well as by Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948).

This is part of the problem with censorship and blasphemy laws. Not only do they interfere with the right to express information, but they also interfere with the right to seek and receive information.

It is also part of the problem with laws, or social media regulations, that prevent open reasonable debate on issues where rights come into conflict, such as the balance between freedom of religion and freedom of expression, and contentious social issues.

4.5 The Right to Nonreligious Philosophical Convictions

There is an established internationally recognised human right to be atheist, agnostic, secular, humanist, or in any other way free from religion. This human right is part of the fundamental right to freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief. It applies equally to all persons, including persons with non-theistic and atheistic beliefs and supporters of secularism.

In 2019 the International Commission of Jurists, composed of 60 judges and lawyers from all regions of the world, published a Primer on International Human Rights Law and Standards on the Right to Freedom of Thought, Conscience, Religion or Belief. Its opening paragraph unambiguously states that this is a wide-ranging right:

“encompassing the right to freedom of thought and personal convictions in all matters, and protecting the profession and practice of different kinds of beliefs, whether theistic, non-theistic or atheistic, and the freedom not to disclose one’s religion or belief. International law also guarantees and protects the right not to have a religious confession.”

Authoritarian theocrats frequently breach this right in practice. Islamist States enforce religious dogma and persecute atheists, dissident Muslims, and religious minorities. The Vatican claims to be a State when it suits, then evades human rights obligations by switching to claim to be a religion with its own rules.

These theocrats also deny that this human right exists, citing Catholic Canon Law or the Sharia-based Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam. But the primacy of universal rights is enshrined in the key international human rights Treaties and associated Court judgments and must be upheld.

4.6 The Situation in Ireland

The Irish Constitution does not explicitly protect freedom of thought. However, it does explicitly protect freedom of expression, conscience and religion, and those freedoms flow from and imply the right of freedom of thought.

In a 2011 High Court decision on blood transfusion for a baby, Mr Justice Hogan read into these provisions an implicit protection of freedom of thought, which covers both philosophical and religious thinking. He said:

“Along with the guarantee of free speech in Article 40.6.1, Article 44.2.1 guarantees freedom of conscience and the free practice of religion. Taken together, these constitutional provisions ensure that, subject to limited exceptions, all citizens have complete freedom of philosophical and religious thought, along with the freedom to speak their mind and to say what they please in all such matters.”

Articles 12, 31 and 34 of the constitution include obligatory religious oaths for the President, judges, and members of the Council of State which includes the Taoiseach (Prime Minister), Tanaiste (Deputy Prime Minister), Chief Justice, President of the High Court, chairs of the Dail and Seanad, and Attorney General. These oaths effectively preclude conscientious atheists and agnostics from holding these important positions.

In 2014, the United Nations Human Rights Committee told Ireland: Ireland should amend articles 12, 31 and 34 of the Constitution that require religious oaths to take up senior public office positions, taking into account the Committee’s general comment No. 22 (1993) concerning the right not to be compelled to reveal one’s thoughts or adherence to a religion or belief in public.

In 2020, the Irish Government decided to remove the requirement to swear a religious oath or ask to make a secular affirmation when making affidavits for court cases. This requirement remains for witnesses and jurors who are present at court cases, thus both breaching their human right to freedom of conscience and potentially biasing jurors for or against them.

In 2012 the Civil Registration Act was amended to allow secular bodies to nominate solemnisers for civil marriage ceremonies. This Act overtly discriminates between religious and secular bodies on a number of grounds.

Atheist ex-Muslims in the Irish asylum process face two particular problems. One, the state sometimes insists that they are still Muslims who are safe to be sent back to states where they would be in danger. Two, the lack of privacy in Asylum Centres puts them in a perilous position as they must hide their beliefs from some Muslim asylum seekers.

4.7 The Irish Education System

The Irish State carries out its obligation to provide education by delegating the running of schools to religious bodies that are allowed to run the schools in accordance with their religious ethos. These schools have exemptions from the Irish employment and equality laws that allow them to discriminate on the ground of religion against students, parents, and teachers.

The Irish education system cedes control of most publicly-funded schools to patron bodies, almost all religious. Nearly 90% of state-funded public primary schools are run solely by the Catholic Church. Most of the remaining primary schools are run by minority faith churches, or by a nonreligious patron body called Educate Together.

Nearly half of all state-funded public second-level schools are run by the Catholic Church. Most of the rest are run by state Education & Training Boards and are described as multi-denominational, but many of these are run in partnership with the Catholic Church or the Church of Ireland. There are currently no fully secular or non-denominational schools in Ireland.

These patron bodies are allowed to determine the ethos of the school, which in most cases is Catholic, and that ethos permeates throughout the whole school day. Even many schools directly run by the state, under Education & Training Boards, have a Catholic ethos and engage in “faith formation”. The Oireachtas (parliament) Education Committee has concluded that multiple patronage and ethos as a basis for policy can lead to segregation and inequality, and that the objectives of admission policy should be equality and integration.

In most Irish schools, children are encouraged to publicly express their beliefs, and the beliefs of their families, in an atmosphere which promotes a particular religious view, which in most schools is that of the religious majority Catholic Church. Children are also taught to respect beliefs (not merely to respect the right to hold beliefs, but to respect the actual content of the beliefs). No consideration is given to the right to not reveal their or their families’ beliefs. Some children from minority belief families will not want to feel different, so they are susceptible to revealing their beliefs even if they don’t want to.

The ethos of schools permits sex education to be delivered through the lens of the patron body, which in most cases is the Catholic Church. In 2019 the Oireachtas Education Committee recommended, as Atheist Ireland had asked it to do, that the law be changed to remove the role of ethos as a barrier to the objective and factual delivery of sex education curricula. This is the first time that an Oireachtas Committee has recognised that students have a right to an objective education for the State curriculum, even in denominational schools, outside of the patron’s religion or values programmes. The change has not yet been legislated for.

In 2020, Atheist Ireland obtained a legal opinion that the Constitutional right to not attend religious instruction in schools extends to the right to be supervised or given a different subject. This right is not vindicated in Irish schools.

One consequence of the legal opinion obtained by Atheist Ireland is that a teacher is placed in a legal conflict involving their own conscience, with regard to adherence to Section 37 of the Employment Equality Act versus respecting the constitutional rights of the child under Article 44.2.4 to not attend religious instruction, the inalienable rights of parents to respect for their convictions under Article 42.1 and the rights of atheists, humanists, and secularists to freedom of conscience under Article 44.2.1 and personal rights under 40.3.1.